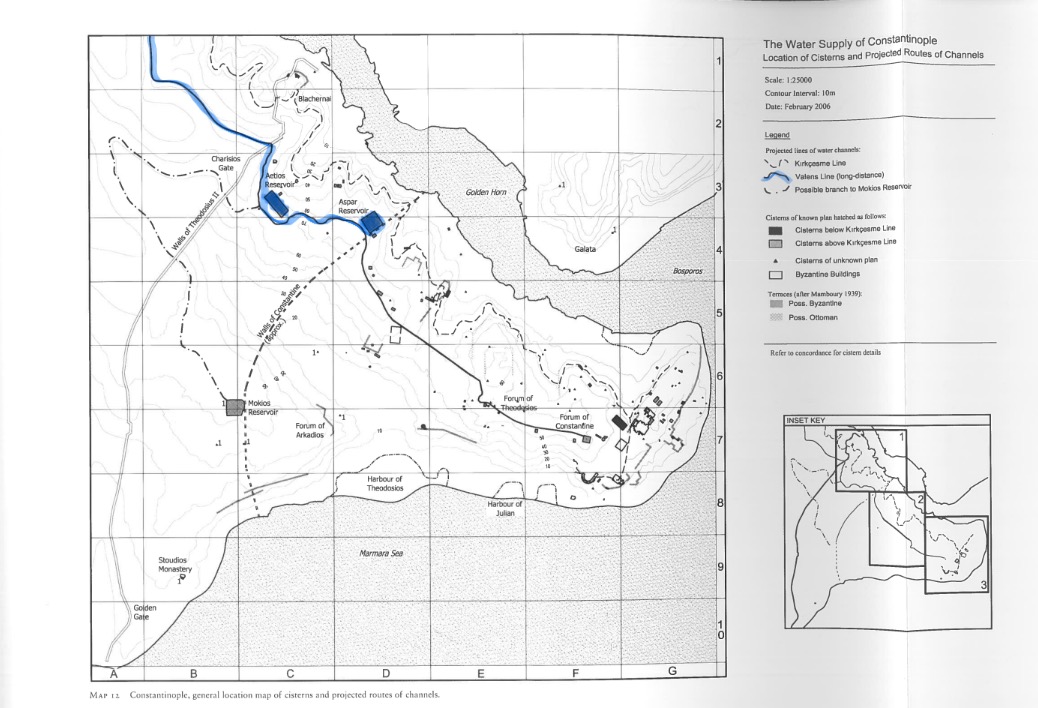

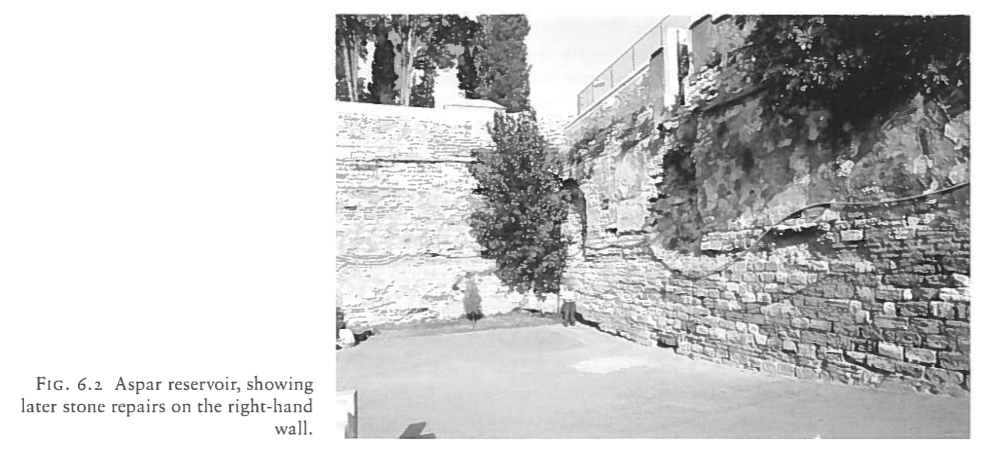

Open reservoir in Region XIV on the Fifth Hill, 152 x 152 x 10-11 m, surface area of 23,100 m2, capacity ca. 250.000 cubic meters. Due to the water pressure of this gigantic capacity, the Reservoir of Aspar could have withstood being filled at most to a depth of 7,5 m (of the 10-11 m). Like the Aetius reservoir, it was built of alternating bands of brick and stone-faced mortared rubble (brick bands: 0,5 m, stone bands, 1.2 m). South-west wall displayed a series of brick arches consisting of two courses of radially-laid bricks about 0,8 m high. Forchheimer and Strzygowski (1893) noted a channel running east from the middle of the south-west flank of the reservoir, likely from the Thrace-channel, supporting the thesis that this reservoir was supplied by the Valens Waterway. Unfortunately due to the destruction of the uppermost parts of the walls, and the debris on the lowest levels, in- and output channels are not visible today. According to Crow et al., the water likely entered the cistern at a level higher than the highest intended capacity (10-11m) (Crow et al., 2008, p. 123, 127-130).

Major cisterns like these (Aetius, Aspar) seem to have been built alongside the new high level water supply on purpose. The reservoir of Aspar's location between the Constantinian and Theodosian walls, as well as the fact that it is an open cistern, suggests that the water was used for agriculture. There are also smaller closed cisterns located nearby, which may imply that these regulated the flow from the reservoirs (Crow et al., 2008, p. 123, 129, 131).

Literary evidence

The construction of the cistern is mentioned in the 7th-century Chronicon Paschale. Janin, 1964, p. 204-205 mentions "Life of Saint Matrone and the Act of the Council of Constantinople 536 and the "le Synaxaire" as sources of evidence that this cistern was located near the Constantinian walls (EDITORS: check).

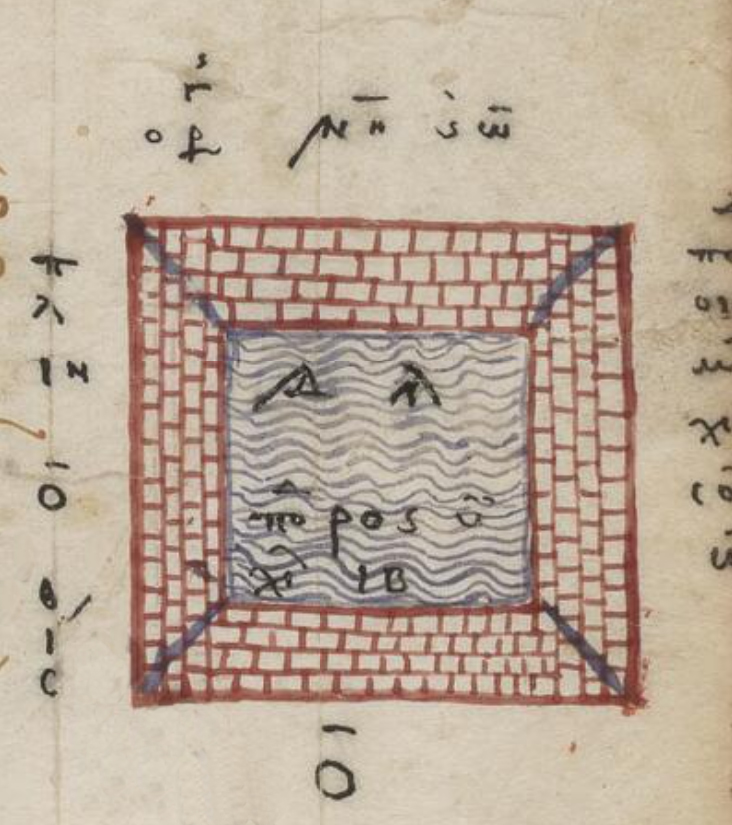

Hero of Byzantium's Geodesia manuscript still shows the reservoir of Aspar filled with water; it might merely be a convention, or evidence that it was still in use (Crow et al., 2008, p. 131-132). The same Hero of Byzantium measured the dimensions of the reservoir of Aspar in the 10th century (Geodosia 9).

At the end of the 10th century, a cylindrical tower was built in the north corner of the reservoir, presumably to lower the water pressure. This tower does not survive into the present day.

In the 13th century, Nikolaos Mesarites describes in the vicinity of the Church of the Holy Apostles "inexhaustible treasures of water and reservoirs of sweet water made qual to seas". Crow et al. comment that this may refer to one of the four reservoirs, amongst them the reservoir of Aspar (p. 240).

In the late 14th-early 15th century, Manuel Chrysoloras wrote from Italy about the lamentable state of the waterworks in Constantinople - with rhetorical exaggaration. About the reservoirs, he wrote: "...and the reservoirs (dexamenai) that received them [channels] once and at that time at least played the part of the seas and lakes for them, either covered and invisible or open and visible, which could be sailed on with ships" (Epistula ad Johannem imperatorem). However, Chrysoloras was of course not in Constantinople itself, and his account cannot be taken as an attestation that the reservoirs were out of order.

In the late 15th century (Codex Matritensis Graecus), the Reservoir of Aspar was still listed as one of Constantinople's highlights, revealing that this cistern had not lost its name over time like many other cisterns.

Gilles (mid 16th-century) describes the reservoir of Aspar as "...a very large cistern in a pleasant meadow, which is despoiled of its roof and pillars." (De Topographia Constantinopoleos 4.2). Could this imply that Gilles thought this cistern was built like a covered cistern (i.e. with a ceiling and pillars)?

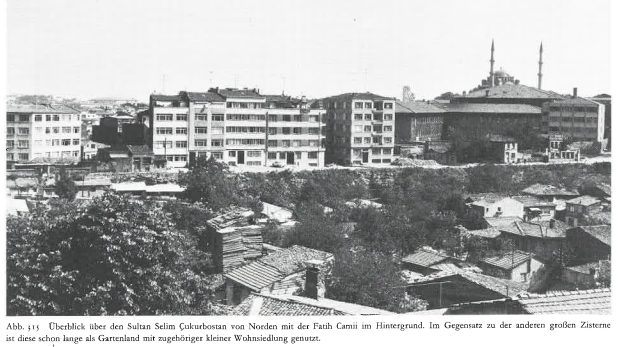

During the 16th century, Süleyman I built a small mosque in the cistern, which had been dry for a long time at that point.

In the 19th century, von Hammer claims that the Cistern of Aspar ("Bodrun dschamissi") lays near Laleli mosque, and had columns of white marble. He thought that Aspar and Ardaburius were two people that were killed by Leo I, and that their blood coloured the water of the cistern (Constantinopolis under der Bosphoros Volume I, p. 557). The name "bodrun" and location may imply that von Hammer identified Myrelaion Cistern as the Reservoir of Aspar. In the late 19th century, Forchheimer & Strzygowski (1893) confirm that a small mosque stood in the Reservoir of Aspar.

The buildings that emerged within the reservoir have been cleared. Nowadays, the Reservoir of Aspar hosts a park and a children's school (Çarşamba Çukurbostan Parkı).