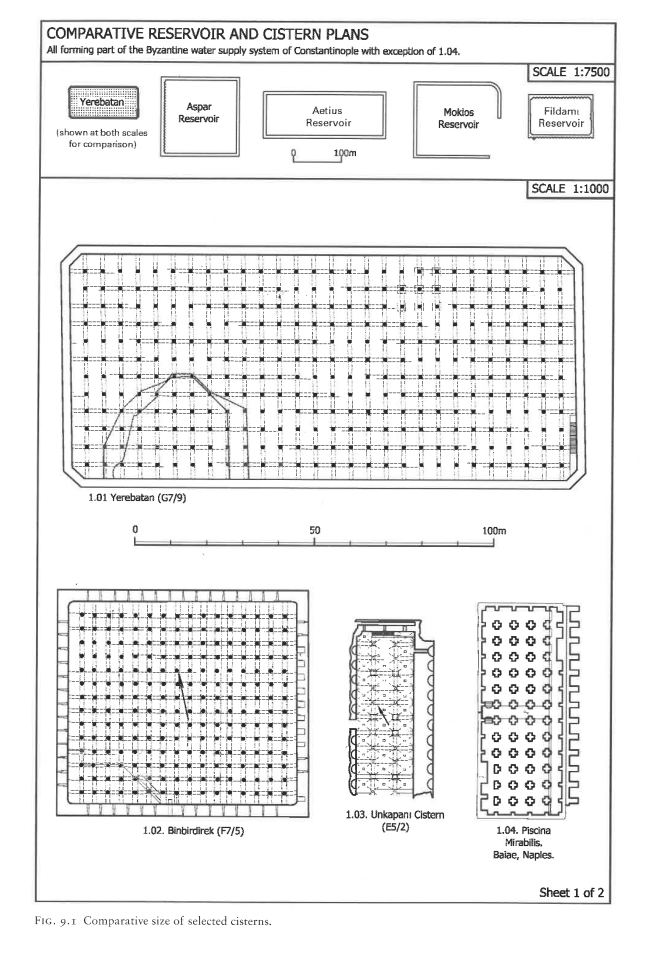

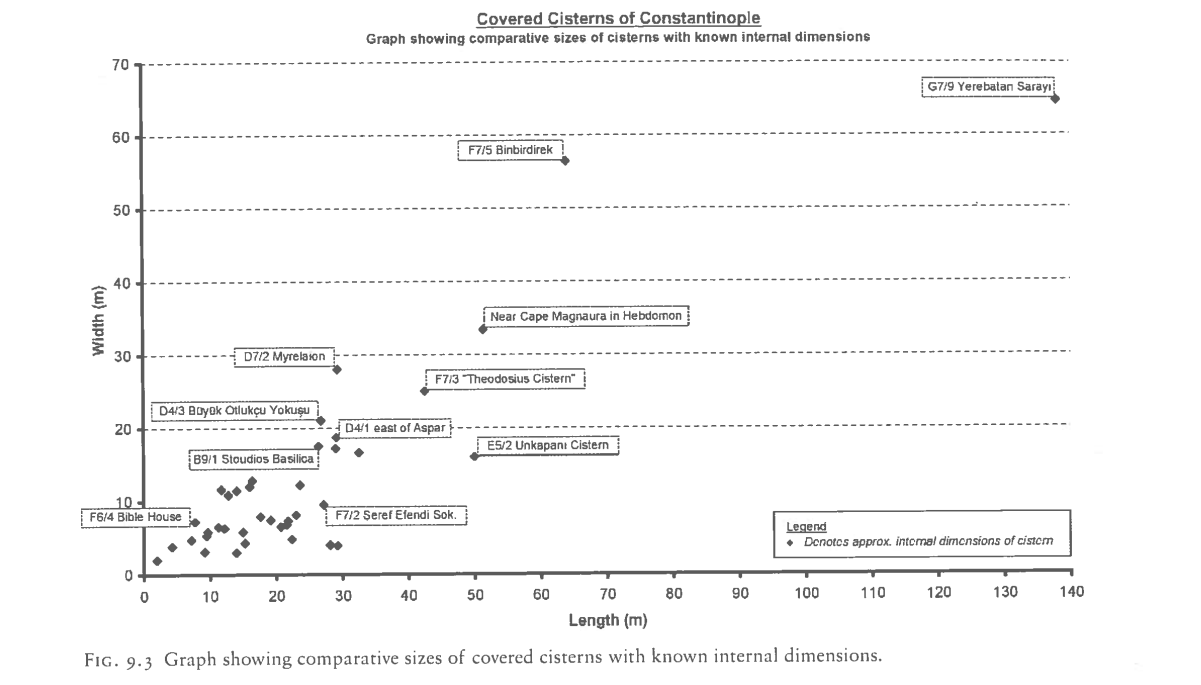

The rectangular plan measures 138 m × 64.4 m, which puts the storage capacity to c. 80,000 tons of water. It contains 336 columns (all of 9 m height). They are 4.80 m apart from each other, organised in rows of 12 × 28 columns. The cross vaults with round arches between columns consist of square bricks of 38-40 cm width and 4 cm thickness, held together by Khorasan mortar (Altuğ, 2013, p. 194). Khorasan mortar can be found in the Roman, Byzantine, Seljuk and Ottoman periods alike, and was famed for its water resistance (Uğurlu, 2005). The cistern bricks are approximately 6-7 cm; the floor is tiled with baked bricks of 40 × 40 cm. Like other cisterns, the corners are rounded against inward pressure (Altuğ, 2013, p. 194). Even though people most likely accessed the water in the cistern as if drawing water from a well through the shaft, the Basilica cistern also had stairs for maintenance (Crow et al., 2008, p. 140).

A large portion of the capitals is reused, and their styles vary. Most columns are topped by plain basket capitals; 98 carreid acanthus capitals; 3 are reused Corinthian capitals (dating to 200 CE and Constantine?). The Basilica cistern also contains a 4th-century column shaft with a lopped branch design and the inverted Medusa heads (Severan date?) (Crow et al., 2008, p. 138).

This large underground cistern was built by Justinian in the 6th century, and is elevated about 30 m above sea level. It was connected to the Hadrianic line alongside the imperial palace (east of the Hippodrome). See Cod. Just. 11.42.6. (Crow et al., 2008, p. 114). In the present day, it is a major tourist attraction/museum owned by the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality. The water level is kept around 1 m. Visitors can explore the cistern on a platform.

Literary evidence

Contemporary accounts of Procopius and Malalas already describe the construction of the Basilica cistern.

In the middle period, the Parastaseis Syntomoi Chronikai and Patria start changing details, such as attributing the foundation to Constantine the Great.

A 10th century Arab account lists "three branches" that brought water into the city (corresponding with the major lines), which includes a line that passed the Basilica Cistern (Crow et al., 2008, p. 20).

In the 15th century, sources (Ibn Battuta mid-14th century; Clavijo beginning 15th century; Buondelmonti beginning 15th century; Zosima the deacon beginning 15th century; Pero Tafur 15th century) start claiming that a huge lake/cistern was situated under Hagia Sophia, sometimes called "Cistern of Muhammad". Could they be referring to the Basilica cistern?